|

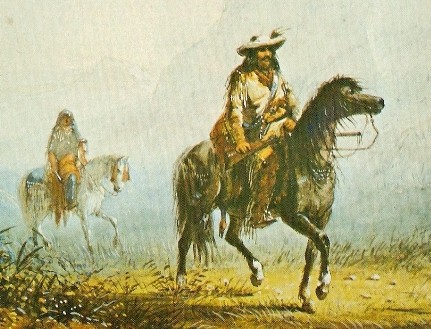

Mountain Men and Spanish Explorers

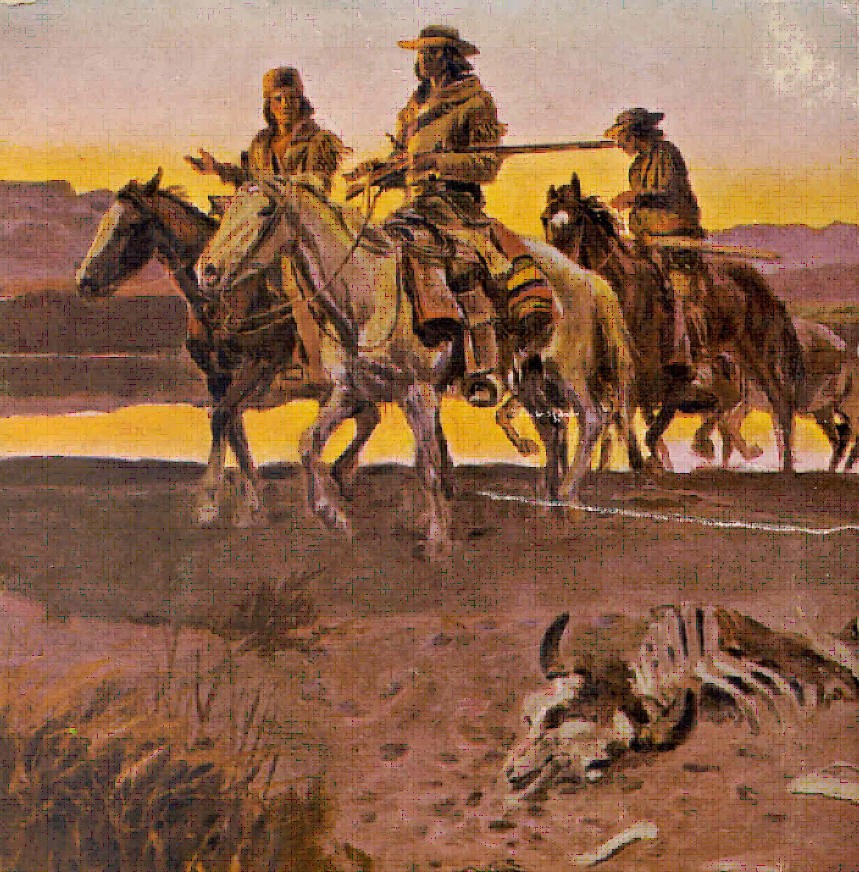

The valley at first was left to the Yokuts, but troublesome fur trappers came in droves in the 1830s, causing great concern to the Mexican authorities. Soon "Yankees" were trapping the length of the valley, most coming by way of Santa Fe, New Mexico and entering the valley through Tejon pass in the south. There were also Englishmen and French Canadians who came down from the Oregon Territory in north. So many Yankees ended up in the northern reaches of the great valley that one of the rivers there became known as Rio de los Americanos, or the "American River".

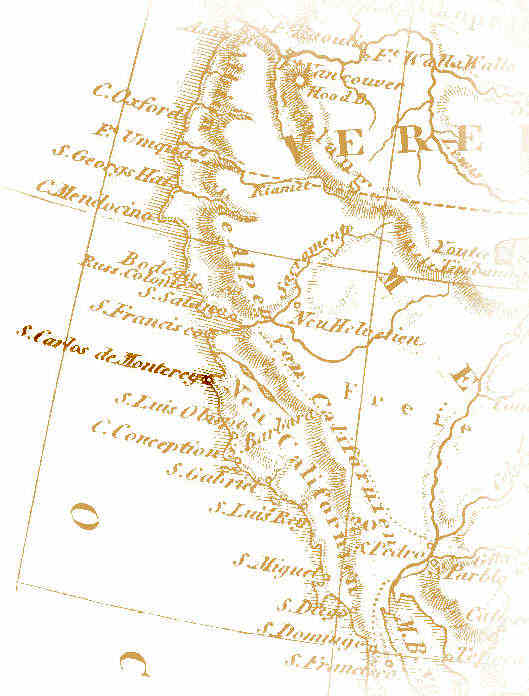

The Spanish Explorers

Next, Lieutenant Francisco Ruiz entered the San Joaquin Valley in 1806 by way of Cuyama Valley and the Carrizo Plain looking for fugitive Indians who had fled the missions on the coast. Father Jose Zalvidea came along to look for possible inland mission sites. When they arrived at the present site of Bakersfield, Father Zalvidea renamed the Rio de San Felipe (future Kern River) to "La Porciuncula," for a Franciscan feast day. The expedition crossed the valley from west to east and left by heading over Tehachapi Pass on the opposite side. Between 1806 and 1813, Lieutenant Gabriel Moraga made several expeditions to the valley, which was known in those days as "Valle de los Tulares", or "Valley of the Tule Grass". Moraga named many of the rivers in the Valle de los Tulares and on at least one of his treks traversed the length of the valley from north to south. In 1808, Moraga entered the Valle de los Tulares from San Jose looking for potential mission sites and runaway Indians. A priest accompanying Moraga named a small creek they encountered after Saint Joachim, the father of the Virgin Mary, and when it was discovered that this creek fed the main river along the axis of the valley, the larger stream acquired the same name. Ultimately, "San Joaquin", which was the Spanish translation for Saint Joachim, was applied to the entire valley.

Jedediah Smith (1799-1831)

The Mountain Man rendezvous provided Smith with a short rest, afterwhich he recruited a new party of 18 trappers to return to Needles. This time the encountered a band of Mojave Indians, who were angry with another group of fur trappers When Smith and his party arrived in San Jose, no heros welcome awaited them there, and they were immediately thrown into jail by the Spanish authorities. Smith was then sent to answer to the governor, from whom he managed to secure the release of his him and party. They next spent the winter of 1827-28 in San Francisco, and rejoined that spring at a camp on the Stanislaus River. Smith and the few remaining trappers of his original party then put California behind them and crossed into Oregon, where they were ambushed by Kelawatset Indians at an encampment on the Umpquah River. Most of the party killed, and only Smith and two or three others escaped to stagger many days later into a Hudson Bay Company outpost at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River. Jed Smith never returned to California, which he did not find suitable for trapping anyway. Self guilt over his neglect of his family over the years led him to sell his trapping interests in 1830 at a Mountain Man rendezvous to the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. He then sought to put his wandering ways behind him, and tried his hand at being a farmer and a merchant. However, these occupations did not hold his interest for very long, and he soon was back at the fur trade. He set out as the guide and leader of a party that was following the Santa Fe Trail, and while scouting ahead looking for water, he was killed on May 27, 1831 by Comanche Indians who caught him alone somewhere near the Cimarron River, close to Philmont Scout Ranch. His body was never found. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ewing Young (1799-1841)

Young returned in 1831 with Carson, joining up for awhile on the American River with a party of trappers from the Hudson Bay Company. Apparently on good terms with the Mexican government, Young's party was able to hunt and trap in the valley unhindered up until 1833, when they headed north along the coast to the Russian settlement of Fort Ross. They then followed Smith's route to the Umpqua River in Oregon, and returned south through the San Joaquin Valley, reaching the San Bernadino Valley in December of 1833.

Joseph Walker (1798-1876)

Whereas Jed Smith, Ewing Young and others had entered California by way of Cajon Pass and the San Bernadino Valley, Walker took a more northerly route, and led his men over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, probably by way of Tioga Pass. On descending the west slope of the Sierras, they discovered Yosemite Valley and camped there on November 13, 1833. One of Walker's men wrote that the Sierra crossing was so diffcult that they took little time "to view an occasional specimen of nature's handiwork." However, he did note that they "saw precipices [that] appeared to us to be more than a mile high."

When the fur market declined in the 1840s, Walker turned to guiding settlers west, and he led many emigrant parties, and two of John C. Fremont's expeditions, into the San Joaquin Valley by way of his now famous pass. When the Chiles family in 1843 rode the first covered wagon into California from the east, they suffered great hardships until Walker found them. Because their wagon could not withstand the rigors of desert travel, they abandoned it, and the Chiles, packing what they could onto their horses and oxen, followed Joe Walker over the pass on foot.

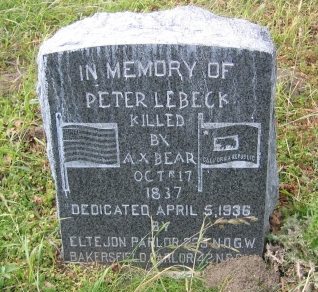

Peter Lebec (d. 1837)

On July 16, 1847, Henry Bigler, Elisha Averett and Daniel Tyler, members of the short-lived Mormon Battalian that had been comissioned as part of the Mexican War effort, were discharged from the U.S. Army in Los Angeles. Immediately, they set out with other battalian veterans for Sutter's Fort in the Sacramento Valley, with the Great Salt Lake as their ultimate destination. While camped in Grapevine Canyon on July 31, Bigler saw the Lebeck inscription on an oak tree they camped near. He described it in his diary and added that, "nearby was the skull and bleached bones of a grizzly bear." Bigler's companion Tyler wrote in his August 1 journal entry, "we ... encamped in a beautiful valley where we found, cut in the bark of a tree, the name of Peter Lebeck, who was killed by a Grizzly bear on the 17th of October 1837. The skull and other bone of the bear, which was killed by Lebeck’s comrades, were still lying on the ground near by. The next day, a ride of fifteen miles brought us to Tulare River [probably the Kern River]. Finding it impassable, we traveled five miles up it and encamped. On August 3rd, Elisha Averett returned from an Indian village, bringing with him several Indians [probably Yokuts], including a chief. A guide was procured from among them and we continued twelve miles farther up the river." Fort Tejon was not garrisoned until Aug. 10, 1854, when it became the first military fort in the interior of California. The bark of the Lebeck oak was starting to cover the bare spot that held the inscription, when Dr. William Edgar, a physician attached to the fort that fall, lived in a tent pitched beneath the oak. He noted the abundance of grizzlies in the area and adds, "I enquired of the Indians living at the mouth of the canada [de Los Uvas], who were the only inhabitants there at the time". He learned that, "many years ago some trappers were passing through the canada, when seeing so many bears one of the party went off by himself in pursuit of a large grizzly and shot it under that tree, and supposing that he had killed it, went up to it, when it caught and killed him, and his companions buried him under the tree, upon which they cut his epitaph." Many theories have been suggested as to the identity of Peter Lebeck, but one of the more likely is that he was a part of a band of men who had thrown in their lot with the French-Canadian renegade Jean-Baptiste Chalifoux. This band, which was known as the Chaguanosos (Shawnee), was in the southern San Joaquin Valley at the time, and probably in Grapevine Canyon. They were mainly French Canadians, with some Indians and Americans from New Mexico, who divided their time between fur trapping and horse stealing. When they took up arms on the side of Mexican authorities in a local conflict, the government promised the Chaguanosos rights to unlimited beaver hunting on all California rivers, of which the Kern River and the lakes of the southern San Joaquin Valley interested the Chaguanosos most. In October 1837, the Chaguanosos raided the Santa Ynez mission, which sits about 75 miles from Grapevine Canyon. A probable route from the southern San Joaquin Valley, where Chalifoux and his men were known to be camping, to Santa Ynez, goes up Grapevine Canyon, around Mt. Pinos by way of Lockwood Valley, then through the Cuyama Valley and down Foxen Canyon and to the mission. If Peter Lebeck indeed was a member of the Chalifoux gang, then it is possible he encountered his grizzly bear either to or from this, or another raid. A Bakersfield group calling themselves the Foxtail Rangers removed the bark from the Lebeck oak in 1889 and found the inscription in reverse on the underside. They returned the next year, and digging around the base of the tree, found the body of a man, about six feet tall and missing the right forearm, left hand, and both feet, indicating Lebeck may have been chewed on by a bear. They reburied the body in its grave, and then returned in 1938 to place a proper headstone over it.

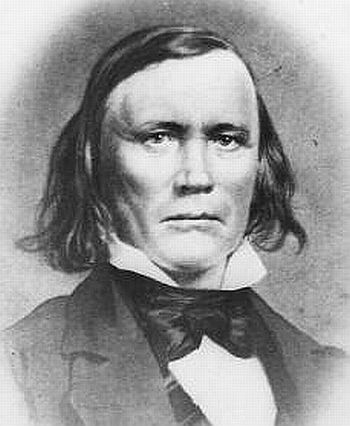

Kit Carson (1809-1868)

Fremont was back in the summer of 1845 with both Walker and Carson. Another member of this trip was Edward Kern, who had hired on as a topographer. At Walkers Lake on the east side of the Sierras, the party split up with Walker leading Kern and most of the others south through Owens Valley and over Walkers Pass, while Fremont, Carson and 14 others headed into the Sierras. Kern's party intended to meet Fremont on the South Fork of the Kern River. However, Fremont, always the adventurer, made a harrowing crossing instead of the the northern Sierras, over what later became known as Donner Pass. While Walker headed back to santa Fe, Kern waited 22 days for Fremont at the present-day site of Isabella Dam, which allowed the topographer to fully explore the valley that now bears his name, discovering a gold nugget in the process at Greenhorn Cave. Eventually, Fremont and Kern rejoined at Hartnell Ranch in the Salinas Valley, and Fremont honored the topographer by naming the Kern River after him, and in so doing renaming the Rio de San Felipe of Francisco Garces. | |||

The San Joaquin Valley of the Yowlumne Yokuts was a much different valley than the one we know today. Teeming with fish and wildlife, it was a great expanse of prairie grasslands and tule grass marshes, with lakes hundreds of square miles in size strung out along the valley axis. The abundant game beckoned trappers and mountain men.

The San Joaquin Valley of the Yowlumne Yokuts was a much different valley than the one we know today. Teeming with fish and wildlife, it was a great expanse of prairie grasslands and tule grass marshes, with lakes hundreds of square miles in size strung out along the valley axis. The abundant game beckoned trappers and mountain men.